The disaster described below was once the one most often cited by pilot-training schools as an example of the dangers of precipitous action.

British Midland Flight 92, January 8, 1989

Pilots around the world were incredulous; some even thought Boeing might have connected the instruments the wrong way around. If not, how could experienced pilots make such a mistake, confusing right with left? In addition, the pilots had believed there was a fire when there was no fire.

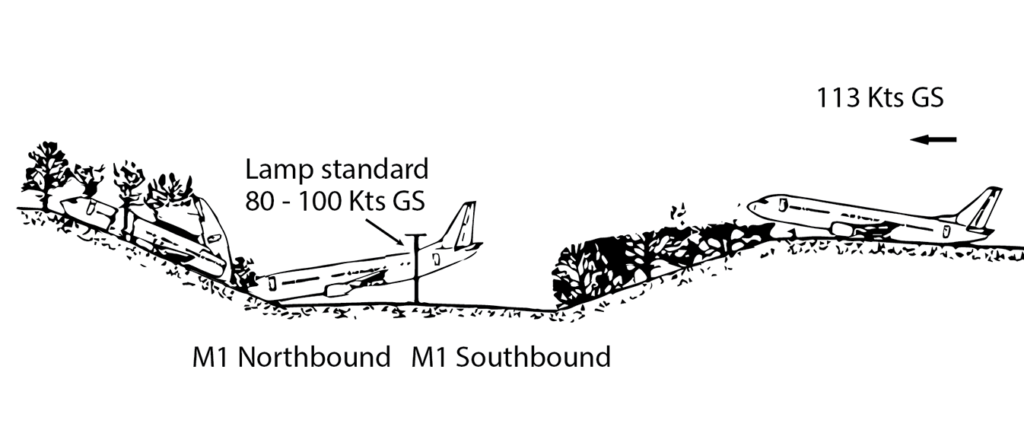

The early-evening British Midlands Airways 737 flight from London to Northern Ireland was at 28,300 feet and climbing under rated power toward its cruising height of 35,000 feet. Then, thirteen minutes after takeoff, there was a loud bang, followed by a thumping noise and vibration. Passengers in the rear of the aircraft were disturbed to see flashes issuing from the tailpipe of the number one engine on the left—very apparent in the wintry darkness. Smoke or something like it then started coming in through the air-conditioning.

Pilots can observe events in front of them but not nearly so easily see what is happening to the aircraft and engines behind them. There are plans to install mini–TV cameras everywhere, both for technical reasons and as an antiterrorist measure, but for the moment pilots have to rely on their instruments in the first instance, and perhaps later on reports from cabin crew and passengers. The pilots felt the shudder and vibration and heard the noise. The captain later said he smelled and saw smoke coming in through the air-conditioning; the first officer just noticed the smell of burning.

The captain immediately disengaged the autopilot and took over control, according to standard procedure. He then asked the first officer which engine was giving trouble.

The first officer replied:

It’s the lef— . It’s the right one.

To which the captain replied:

Okay, throttle it back.

The captain later said he thought the smoke was coming in from the passenger cabin, and, based on his erroneous knowledge of the way the air-conditioning on that model of the 737 was designed, concluded the smoke must be coming from the right-hand engine. In fact, he could not have been sure where the smoke was coming from.

Whatever the facts, this meant the first officer was confirming what the captain already thought. The captain gave his order to throttle back the right engine nineteen seconds after the onset of the vibrations, so we are talking about a short time frame and little opportunity for reflection or study of the instruments.

When questioned later, the first officer could not say which instrument indication made him conclude it was the right engine. From the exact words of the first officer, it would seem that the first officer was not sure but felt obliged to give an answer. Could he have subconsciously sensed the answer the captain expected? Otherwise, why would he switch from “lef—” to “right”?